By YAN Fusheng

Sometimes chemistry doesn’t just make new molecules—it overturns old assumptions. For 140 years, drugmakers have accepted that transforming aromatic amines—a very important reaction for building drug molecules—means living with explosive risks. The danger was considered unavoidable, the tradeoff permanent—until a team in Hangzhou proved otherwise.

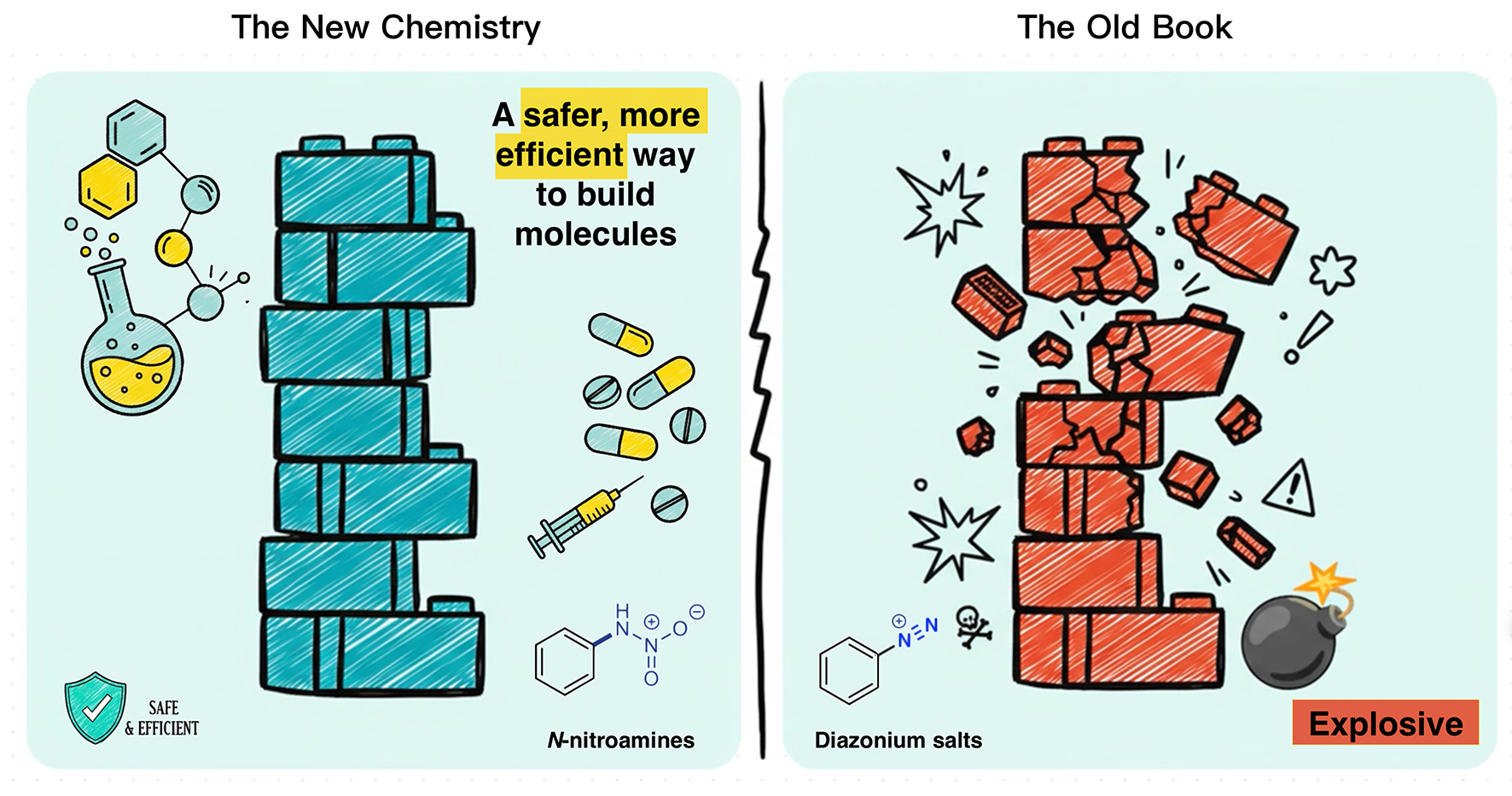

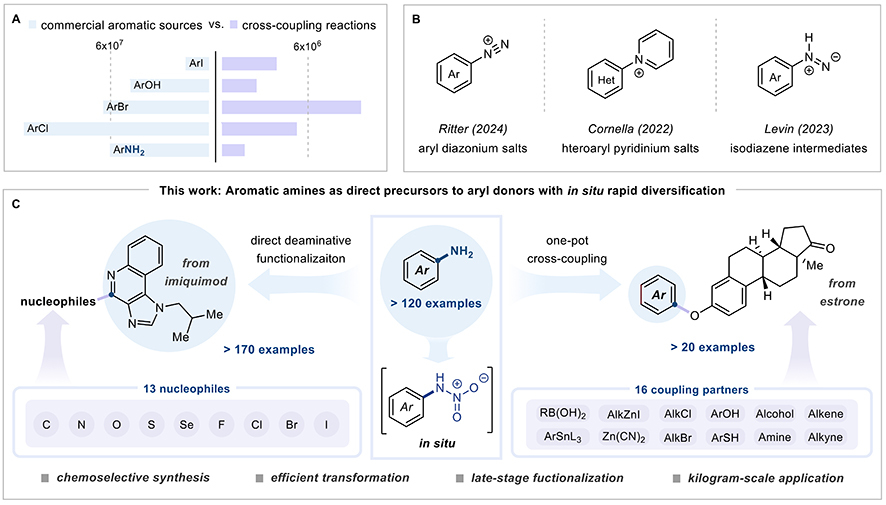

After tolerating an explosive but “necessary” intermediate for over 140 years, chemistry finds a safer path forward: Aromatic amines serve as foundational building blocks for drug molecules but transforming them has required explosive diazonium salts since the 1880s (right panel). Now, a rediscovered chemistry using N-nitroamines offers a safer, more versatile, and more practical way (left panel) to break C–N bonds and replace them with other functional groups. (Graphic: YAN Fusheng)

For over a century, pharmaceutical chemists have lived with an uncomfortable truth: Making many life-saving drugs requires dancing with explosives. Diazonium salts, the chemical they rely on to transform aromatic amines—nitrogen-containing molecular frameworks found in roughly half of all medications—are so unstable that a 1969 incident at Ciba AG in Basel destroyed a building, killed three workers, and injured 31 others.

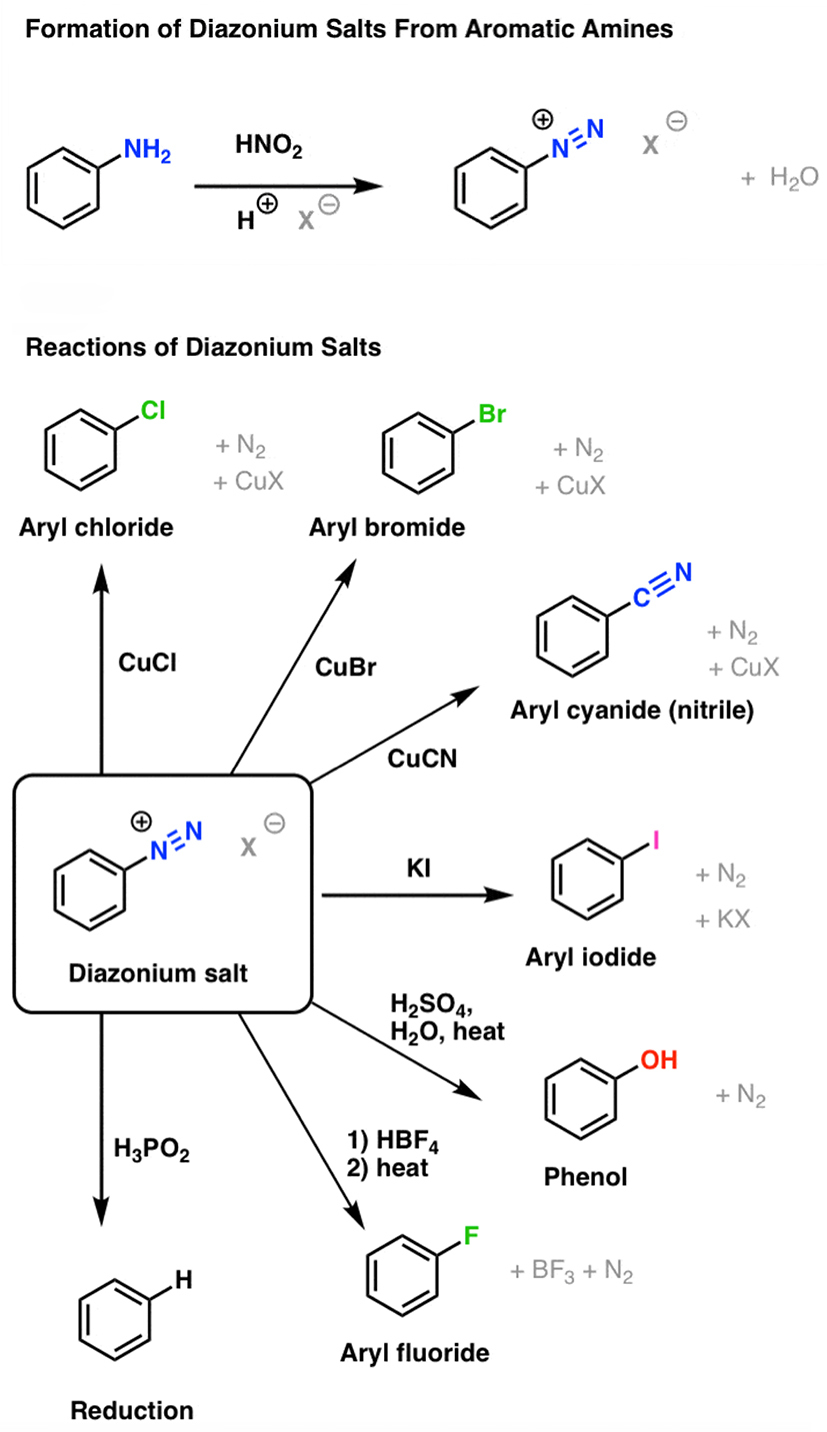

Despite 140 years of use since Traugott Sandmeyer first showed in 1884 that these salts could transform amines into aryl halides and other functionalities using copper salts, the chemistry remains as dangerous as it is indispensable.

Until a research team in Hangzhou stumbled upon something they weren’t even looking for.

The aromatic diazonium chemistry converts aromatic amines into unstable, explosive diazonium salts that mediate deaminative functionalization, which is widely used in pharmaceutical intermediate synthesis. (Courtesy from James Ashenhurst/Master Organic Chemistry)

The Failed Experiment That Worked

Dr. ZHANG Xiaheng’s group at the Hangzhou Institute for Advanced Study, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, had a straightforward goal: Weaken the bonds holding nitrogen to aromatic rings so they could swap out aromatic amines like interchangeable parts. Their strategy made perfect sense—install electron-withdrawing groups to loosen nitrogen’s grip by pulling its electrons away.

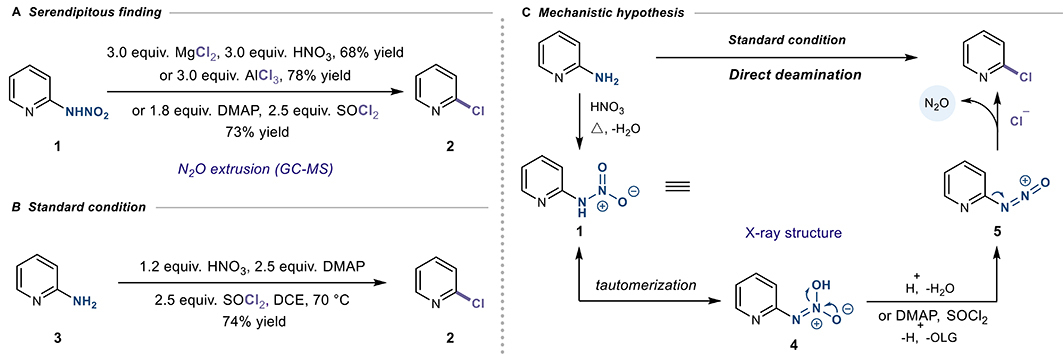

The researchers expected incremental progress at best. Trifluorosulfonyl modifications yielded nothing. Acetyl groups proved a dead end. Benzoyl substituents struck out. Then they tried nitric acid—and everything changed.

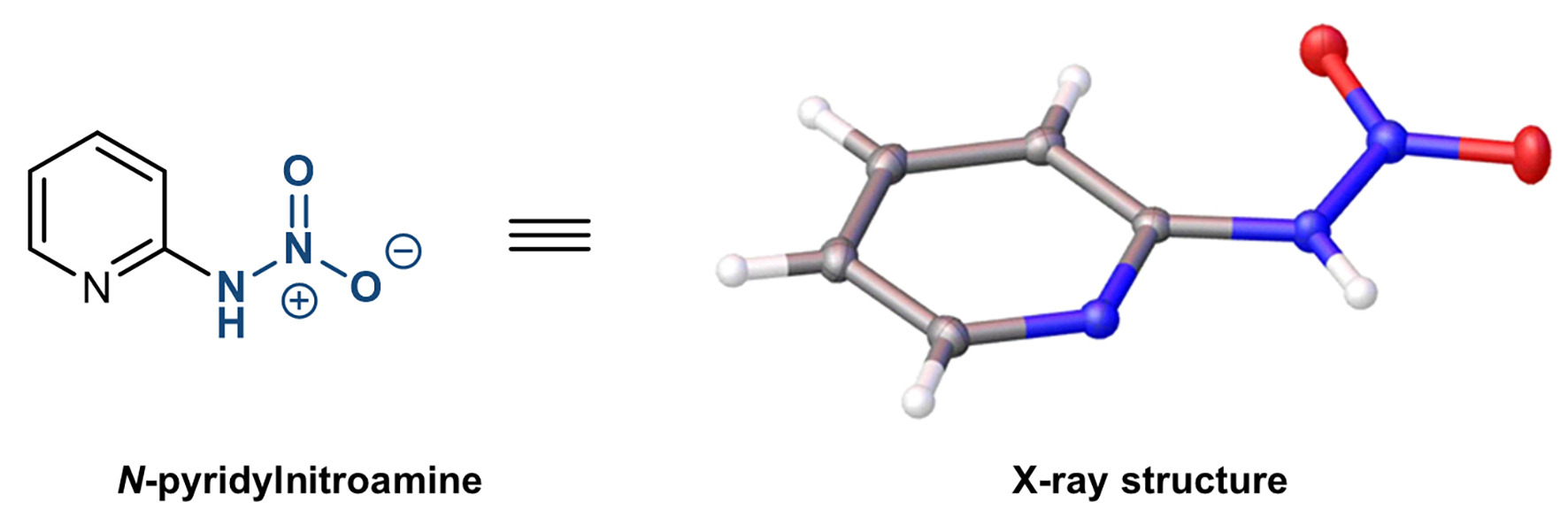

Instead of their expected products, the researchers found something crystallized from the reaction mixtures. They performed X-ray crystallographic analysis to confirm structures and confirmed them as a group of compounds called N-nitroamines.

Their breakthrough began with investigating unexpected crystals formed in their experiments. (Image by courtesy of Dr. ZHANG)

These compounds had been sitting in chemistry textbooks since 1893, ignored as useless byproducts. For 132 years, no one had bothered to explore what they could actually do. However, the ZHANG group systematically investigated their reactivity—something no one else had attempted. It turns out these neglected compounds are exactly what pharmaceutical chemistry needs.

From Laughing Gas to Serious Chemistry

The team’s discovery, published in Nature on October 27, offers something the industry has wanted since 1884: A way to functionalize aromatic amines without generating explosive intermediates.

Here’s how it works. Treat an aromatic amine with nitric acid, and you generate an N-nitroamine transient intermediate right in the reaction vessel—no isolation, no handling, no explosions waiting to happen. Add activating reagents like thionyl chloride with DMAP (4-dimethylaminopyridine), and something remarkable occurs: The N-nitroamine releases nitrous oxide (N2O)—laughing gas, the stuff dentists use to relax the patients—while the aromatic ring becomes primed for attack by incoming chemical partners.

The rediscovery of N-nitroamines—stable intermediates that pull off the same molecular magic without the explosion risk, metal contamination, or Byzantine multi-step headaches— are expected to “break the wheel” and advance medicinal chemistry. (Graphic: Tu et al., 2025)

The mechanistic twist makes all the difference. Traditional diazonium salts are highly energetic substances, with decomposition that can become violent when heated above 40°C, scratched with metal spatulas, or exposed to friction or static discharge. Some detonate spontaneously. The N-nitroamine pathway sidesteps this entirely. Instead of releasing nitrogen gas violently, you get mild N2O extrusion. Instead of accumulating unstable intermediates, the reaction moves so fast—complete conversion in 90 seconds—that dangerous species never build up.

Think of it like this: Diazonium chemistry is a pressure cooker with a faulty valve. The N-nitroamine approach is a controlled venting system that never lets pressure accumulate in the first place.

A Promising New Protocol for Pharmaceutical Engineering

The new intermediate paves a safe way out for the synthesis of many medicinal chemicals, hinting to a renewed engineering protocol that might have far-reaching implications in the pharmaceutical industry. This rosy prospect hinges on three notable characteristics inherent to ZHANG’s approach.

First, substrate generality that actually generalizes. The new protocol works across electronically diverse aromatic amines—electron-donating, neutral, and electron-withdrawing substituents at any position—with yields ranging from 40% to 96%. More impressively, it succeeds with multi-nitrogen heterocycles like pyrimidine, pyrazine, and pyridazine where conventional Sandmeyer conditions consistently register as “not detected” in comparative studies. The researchers demonstrated 80-plus successful transformations including medicinally relevant scaffolds from antihistamines, antibiotics, antivirals, and anti-inflammatory agents. When they tested procaine, amlexanox, fasudil, riluzole, and famciclovir—complex drug molecules bearing multiple functional groups—traditional methods largely failed while the N-nitroamine approach delivered products in 41% to 95% yields, showcasing the robustness of this new method for late-stage diversification of drug molecules.

Second, functional group versatility that eliminates method development bottlenecks. A single set of conditions enables carbon-halogen bond formation (C–Br, C–Cl, C–I, C–F), carbon-heteroatom bonds (C–N, C–S, C–Se, C–O), and carbon-carbon bonds directly from aromatic amines. This universality matters because conventional approaches require completely different reagents, catalysts, and conditions for each bond type. Pharmaceutical process chemists juggling portfolios of amine-containing drug candidates can now standardize protocols instead of reinventing chemistry for every substrate—cutting aggregate method development timelines from months to weeks while slashing associated costs by 30% to 50%.

The new chemistry of N-nitroamines that is simultaneously safer, broader, and more practical in breaking the C-N bonds and swap them for others. (Graphic: Tu et al., 2025)

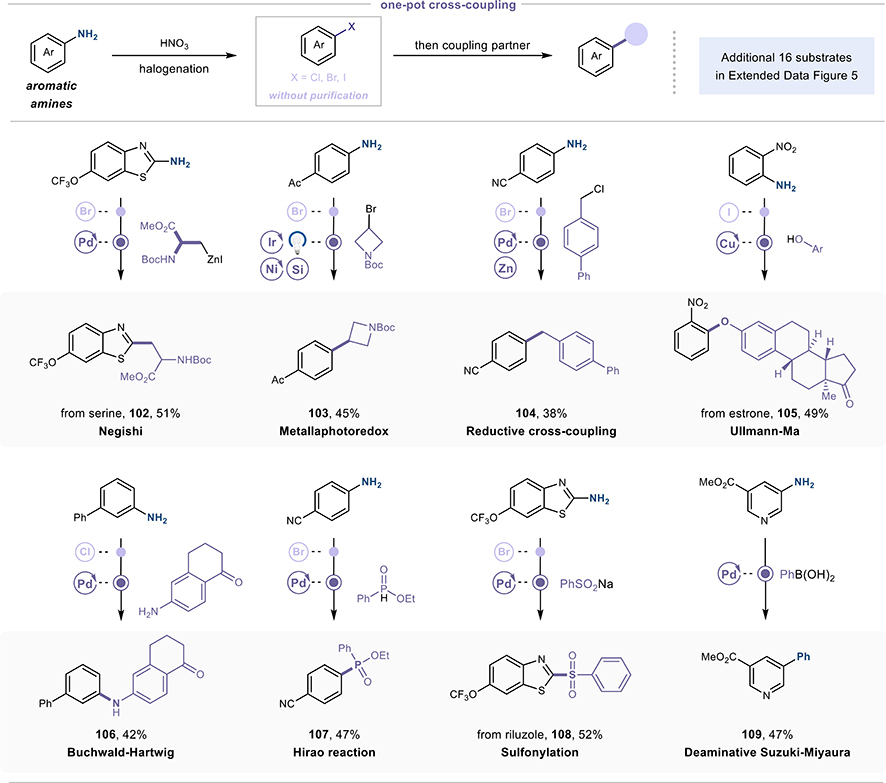

Third, one-pot integration that compresses synthetic routes. ZHANG’s team demonstrated that in situ generated aryl halides proceed directly into transition-metal-catalyzed coupling reactions without intermediate isolation, purification, and solvent switch. They successfully chained deaminative halogenation with Negishi coupling, Buchwald-Hartwig amination, Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, Ullmann-Ma reactions, Hirao phosphonation, sulfonylation, and even metallaphotoredox catalysis—delivering products in 38% to 52% yields over two steps. Each deleted step typically saves 15% to 25% in material costs and 20% to 40% in cycle time. For active pharmaceutical ingredients requiring amine-to-heteroatom transformations, this route compression could translate to substantial gross margin improvements once put at manufacturing scale, implying a compelling economic advantage that positions early adopters to capture significant market share while building competitive differentiation in next-generation synthesis capabilities.

The one-pot cross-coupling via N-nitroamine chemistry compresses synthetic routes and yet offers satisfying yields. (Graphic: Tu et al., 2025)

The Kilogram Test

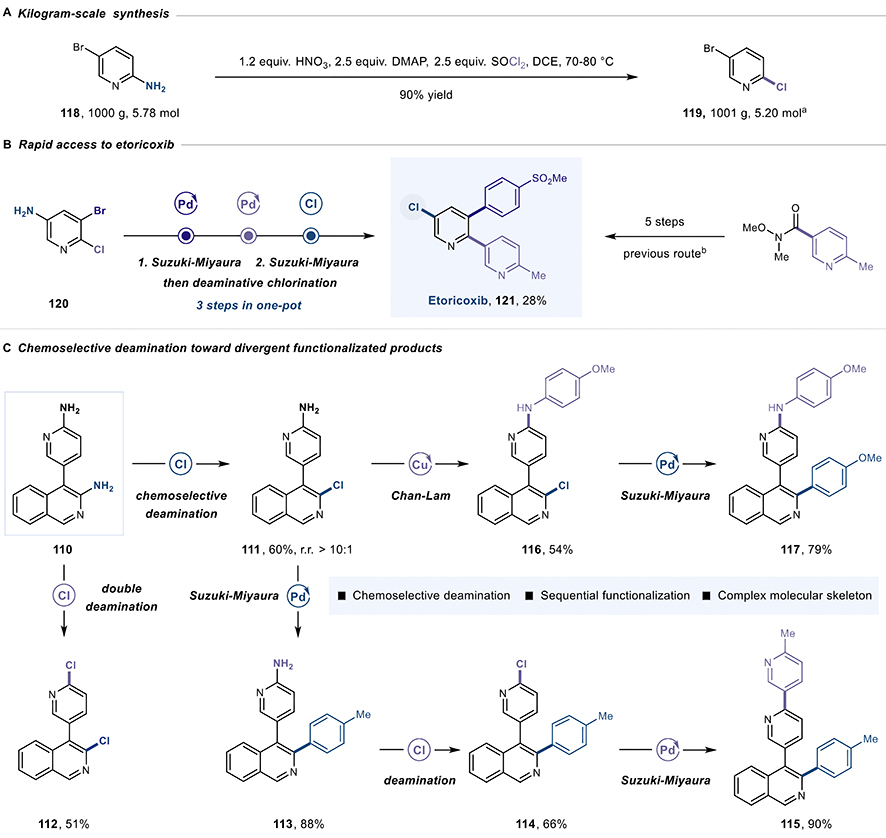

Laboratory discoveries often collapse when scaled up, however. Inconvenient realities—heat dissipation, mixing efficiency, impurity accumulation—assert themselves. ZHANG’s team confronted this directly by processing one kilogram of 5-bromopyridin-2-amine through their protocol.

The reaction delivered 90% yield, purified by simple recrystallization rather than expensive chromatography. This operational robustness matters enormously. Diazonium chemistry demands blast-rated reactors and specialized containment systems, and extensive hazard controls, which are not cheap. By eliminating these investments, such capital expenditure relief could translate directly to cheaper manufacturing and faster technology transfers between production sites.

In another striking experiment, they synthesized the anti-inflammatory drug etoricoxib in three steps, one pot, 28% yield. Conventional approaches requiring isolation and purification between each step would need substantially more time and material.

The researchers pushed further, demonstrating selective control over reactions. Starting with a compound containing two similar amino groups, they achieved mono-functionalization by controlling temperature—or double functionalization by increasing reagents. This selectivity enables divergent synthesis strategies where a single intermediate branches toward multiple target structures.

The kilogram-scale synthesis, rapid access to etoricoxib and selective deamination. (Graphic adapted from Tu et al., 2025)

How It Actually Works

Understanding mechanism matters because it reveals limitations and opportunities. ZHANG’s team ran multiple experiments pointing to aryl cation intermediates as the key reactive species.

When substrates underwent intramolecular C–H insertion—the Mascarelli-type reaction classically associated with cationic intermediates—they formed cyclized products. When they ran the reaction in different solvents, they saw behavior consistent with highly electrophilic (electron-seeking) carbon centers: intramolecular reactions in ethyl acetate, intermolecular reactions in benzene.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provided the quantitative picture. After chloride departure from an activated intermediate, N2O extrusion proceeds with a barrier of only 7.3 kcal/mol—a remarkably low hurdle explaining why conversion happens so rapidly. The resulting aryl cation reacts with nucleophiles before side reactions can intervene.

Importantly, the calculations examined seven different nucleophiles across electronically diverse substrates, and revealed that while strongly electron-deficient aromatics might follow traditional substitution pathways, the aryl cation mechanism dominates for most pharmaceutical applications.

Rethinking Molecular Design

The new approach might fundamentally inspire medicinal chemists in conceptualizing molecular design during drug discovery.

Aromatic amines no longer need precious-cargo protection throughout multi-step synthesis. Instead, teams can intentionally install amino groups as “programmable handles” for late-stage diversification—introduce the amine early, optimize other molecular properties through intermediate steps, then convert that amine into any desired functionality during final diversification.

This design-phase optionality multiplies value during hit-to-lead optimization when chemists need to explore structure-activity relationships around a promising scaffold. Parallel synthesis libraries can diverge from common amine-containing intermediates into hundreds of structural analogs without redesigning routes from scratch for each variant.

Fewer synthetic routes to develop. Faster iteration cycles. More efficient use of medicinal chemistry capacity. The economic implications ripple through discovery timelines and resource allocation.

New Chemistry from “Serendipity”

Scientific progress rarely follows planned trajectories. ZHANG’s team wasn’t searching for deaminative functionalization breakthroughs when they synthesized those initial N-nitroamines—they were investigating how electron-withdrawing groups might weaken C–N bonds through conventional mechanisms.

The serendipitous observation that nitration produced unexpected crystalline compounds could have been dismissed as an experimental artifact. Instead, they recognized potential where the former chemists saw none. They performed X-ray crystallographic analysis to confirm structures. They systematically explored reactivity that nobody else had bothered investigating.

That curiosity-driven investigation produced methodology that’s simultaneously safer, more general, more operationally simple, and more economically advantageous than the explosive chemistry it is expected to replace.

For an industry producing billions of medication doses annually while managing razor-thin safety margins and intense cost pressures, this represents infrastructure renewal with highly profitable returns.

Sometimes the most transformative discoveries emerge not from solving the problems you intended to solve, but from recognizing when experiments fail in exactly the right way—and having the scientific judgment to pursue where that failure leads.

The pharmaceutical industry has tolerated explosive chemistry for 140 years, because such tolerance seemed to be necessary. ZHANG and his colleagues just demonstrated it wasn’t. That realization alone might prove as valuable as the chemistry itself.

References

Elliot V. The Chemistry Accident That Could Reshape Drug Manufacturing. https://www.ctol.digital/news/chemistry-accident-reshapes-drug-manufacturing/#when-explosions-are-just-part-of-the-job

Tu, G., Xiao, K., Chen, X., Xu, H., Zeng, H., Zhang, F., . . . Zhang, X. (2025). Direct deaminative functionalization with N-nitroamines. Nature. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09791-5